Hotspot of the Cold War

US and Soviet tanks at Checkpoint Charlie, 28 October 1961 © U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center

When U.S. and Soviet tanks drove up to Checkpoint Charlie in October 1961, the significance of the divided city as a hotspot of the Cold War became clear once again. In the summer of 1990, the foreign ministers of the four victorious powers met at this same site to negotiate the end of division with the two German states in Berlin. At the very site where the Cold War powers had confronted each other with hostility, they were now demonstrating a willingness to settle the global conflict peacefully.

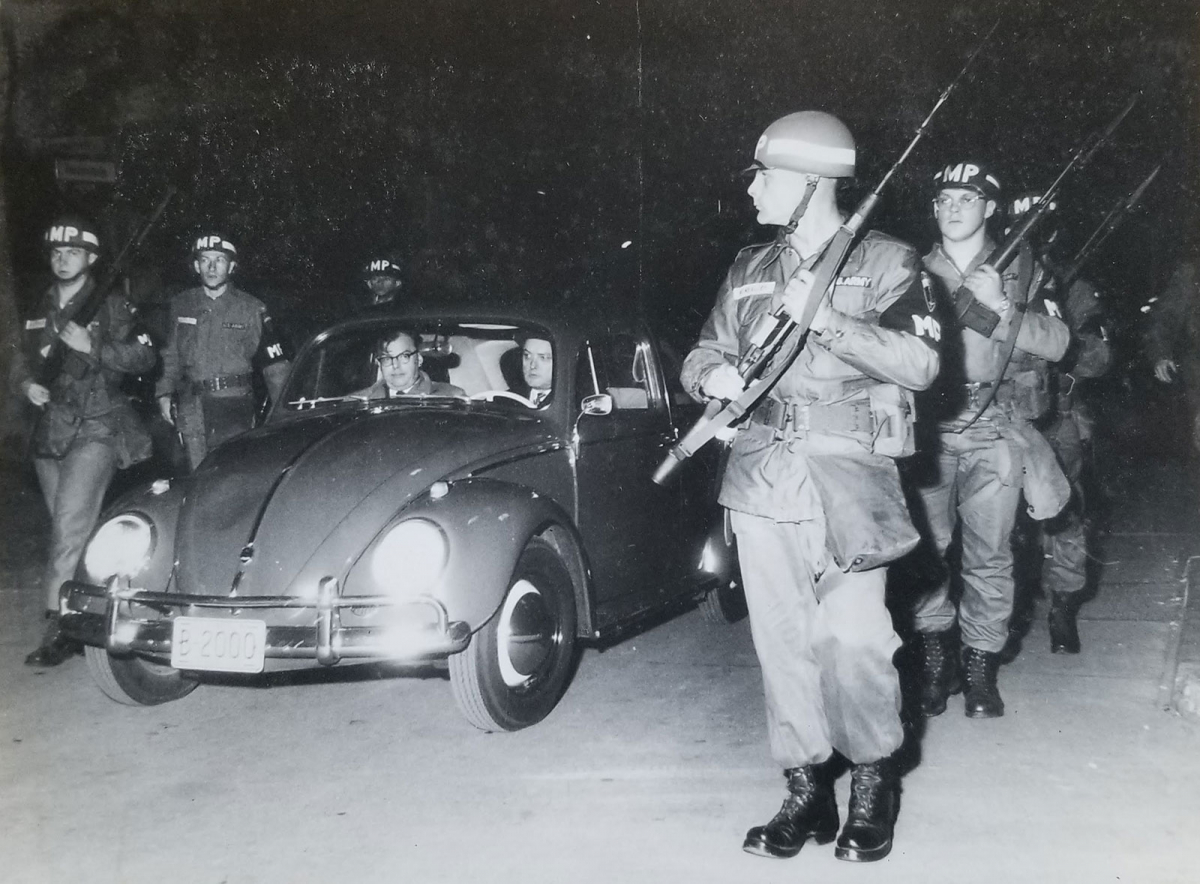

In September and October 1961, the GDR border police repeatedly refused to allow U.S. military personnel in civilian clothes to cross the border unless they showed their ID. This happened to Edwin A. Lightner, the deputy chief of the U.S. mission in Berlin, on the evening of October 22, 1961. He and his wife were on their way to the opera in East Berlin. The GDR border police asked him to identify himself. Lightner refused, insisting on the right of the Western Allies to travel unchecked into East Berlin. Nearly two hours later, he finally passed the border, escorted by U.S. military police with two jeeps and eight armed military policemen.

US military police escort for the deputy head of the US mission in Berlin, Allan E. Lightner, at the GDR border crossing at Friedrichstrasse, 22 October 1961 © US Army/private ownership

As soon as the convoy reached East Berlin territory, it turned around and drove back to West Berlin, only to turn around again, pass through the border crossing a second time and drive back. The third time they did this, Lightner was not stopped. After this incident, the U.S. strongly protested to the Soviet Union. Invoking the four-power status, they insisted on their right to move freely throughout Berlin. The Soviet Union, in turn, pointed to the regulation of the GDR Ministry of the Interior, which stipulated that if members of the Western Allies in civilian clothes wished to cross the border, they must identify themselves.

Over the next two days, the situation was repeated over and over again on Friedrichstrasse: GDR border police officers prevented members of the U.S. armed forces in civilian clothes from passing and armed U.S. military police arrived to escort them through the border crossing. But on October 25, the U.S. turned to harsher measures: It sent ten tanks to Checkpoint Charlie. Three tanks drove up to the border on Friedrichstrasse and seven more tanks were stationed on the right and left of Friedrichstrasse on grounds directly adjacent to the Wall. The tanks withdrew in the evening but drove back the next afternoon and stayed for an hour.

US soldiers on a tank during the tank confrontation at Checkpoint Charlie, 1961 © Berlin Wall Foundation, Gerhard Neumann

On October 27, the situation tensed as word spread that Soviet tanks had arrived in East Berlin the previous night. Once again, U.S. tanks drove up to Checkpoint Charlie and withdrew a short time later. When the last American tank had left, ten Soviet tanks drove up to the East Berlin side of the border crossing for the first time. Although they withdrew a few minutes later, the situation came to a head: The U.S. tanks had been alerted and returned to Checkpoint Charlie. The Soviet tanks came back too. Shortly after 6 p.m., the two Cold War enemies faced each other in a menacing standoff in the middle of Berlin.

News and pictures of the tank confrontation spread quickly. Many journalists and hundreds of spectators had been following the events for days on the ground at Checkpoint Charlie.

The confrontation ended as quickly as it began. The next morning, after 16 hours, the Soviet Union withdrew its tanks and the U.S. tanks followed shortly thereafter. In secret negotiations, the two superpowers had agreed to end the sabre rattling, which had attracted so much media attention.

Watch here how experts discussed the background of the conflict and its role during Cold War. Was it just sabre rattling with media effect or was the world on the brink of a new war?

On the morning of June 22, 1990, a military ceremony was held during which the control booth of the Western Allies was removed from Checkpoint Charlie. This symbol of the Cold War in Berlin had become superfluous.

Deconstruction of the allied control booth, 22 June 1990 © Alamy

The date was not insignificant: On that day the international Two Plus Four Talks about German unity were continuing in East Berlin. The foreign ministers involved in the negotiations, from the United States, the Soviet Union, France, Great Britain, the Federal Republic and the GDR, attended the ceremony together. Afterward, they negotiated the future sovereignty of a unified German state at the Schönhausen Palace in East Berlin. The meeting was an important step on the way to the Two Plus Four Treaty, which was signed in September 1990, sealing the end of Germany’s division.